Description

Mao Meets Muddy documents a trip Ramos made to Beijing to accompany his good friend, painter Frederick J. Brown, for a retrospective of Brown’s work at the National Museum of China in Tiananmen Square in 1988. It was the first solo exhibition in China of a Western artist, and Ramos sets the stage by narrating in voiceover his personal and inherited views of the country and its politics, molded by the xenophobia of his childhood in the Cold War 1950s. Countering this, Ramos explores the prospect of and precedent for solidarity between Communist China and Black people in America, represented by the occasion of Brown’s exhibition.

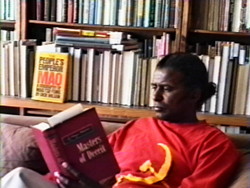

In an opening scene, Ramos introduces himself as a symbol and subject of American fear-mongering, lounging poolside in Los Angeles dressed in a red t-shirt bearing the communist movement’s hammer and sickle, reading former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s Masters of Deceit: The Story of Communism in America and How to Fight It (1958). Ramos lingers on a section denouncing communist views on the self-determination of Black people in America, situating Hoover’s treatise within a larger white supremacist agenda.

Once in China, Ramos finds hope in the very prominent honoring of Brown – an “African-American, Cherokee, steelworker’s son from Chicago” – in a national building in Tiananmen Square. During the show’s installation, Ramos shows the Chinese and American crew enjoying a common language of music, dance, and sport. While a boom box echoes Muddy Waters and hip-hop in the cavernous marble halls of the museum, itself a product of 50s-era nationalist monumentalism, crew members dance and play football. In one scene, a Chinese man practices pop-and-lock moves in front of Brown’s large portrait of blues singer Bessie Smith (Brown is known especially for his portraits of jazz and blues figures).

Brown’s exhibition opens with a joyful media blitz and much fanfare, inspiring Ramos to wonder in voice-over if, now that Mao has met Muddy, a new era of openness and greater creative freedom has begun. The retrospective position of his video captures the shattering of this vision. The student protests and subsequent massacre of civilians in and around Tiananmen Square a year later, delivered through the frame of American television, only reinforced long-standing divisions and systemic oppressions. A journey forward instead becomes a return to a world divided; Ramos concludes by recording himself looking directly into the camera, crestfallen, a witness to a humanity sacrificed for nationalist agendas, and lost in television’s structured reportage.

This title was recently preserved by Bill Seery, Director of Preservation Services, The Standby Program, with special thanks to the Collection of the Frederick J. Brown Trust.